It must have been sometime in 2017, when I was going through a lecture series on Taittiriya Upanishad, which deals with education, I had a life altering experience that changed my worldview on education. It spoke about what students must learn and underlined the superiority of experiential learning, as well as assimilation of learning through contemplation.

I compared this to what I advocate when training teachers. A model called experiential learning that was developed in the twentieth century, says that learning happens best when children experience something and review their experience by reflecting. The stark similarity between the two struck me. Taittiriya Upanishad, written a staggering seven thousand years ago in a conservative estimate, said exactly what experts say today. I did start a research on how learning happened in ancient India.

I broke down what the Gurukuls did to their structure and pedagogy, which was my primary interest. It was around this time when COVID 19 happened. We saw first hand the ills of technology, how it could mislead children. Schooling young children in wisdom is important.By wisdom I mean developing the ability to discriminate between the most important and the unimportant as well as the real and make believe.

I realised our aim must be to make them seekers of truth, who can differentiate between real and unreal, truth and untruth, illusion and reality, which is what a Vedantin is trained to do. What I discovered in this journey, is the story of an educational framework known as Contemplative Learning Prakriya.

In ancient India, starting from the Rig Vedic period the Gurukuls aimed at imparting wisdom to the students or disciples, whatever their age. By wisdom, I mean that they aimed at God realisation. The Guru had students of different age groups. He taught them a main text which was the Vedas. This functioned as a guide for students to conduct themselves. In later days, the main text were other treatises that guided them in the study of their disciplines. They were either a text on Mathematics, or Sciences, though the disciplines were not clearly differentiated like today. Someone like Chankaya dealt with governance.

The students did a lot of self study, discussing with other students, debating, arguing on what is reality or what is right, even as they completed all that the Guru had tasked them with. He gave different tasks to students, not the same. By evening, they would clarify their doubts with the guru. Some of the doubts the Guru answered by providing them more experience, not by answering them directly. The deeper the question the better the chances of `passing’ the exam in the Gurukul. There was no formal testing and the Guru focused more on whether they knew the main text well and their attitude.

This means

O. The Guru differentiated in the way each student learned. Today all our teachers engage in what is called differentiated instruction to deal with children of differing abilities and different inclinations.

O. The Guru employed an inductive learning approach by not giving answers directly, but by allowing them to check for themselves and draw conclusions. They did have deductive learning as well when they studied their main text. The two approaches blended in the system, while we struggle to deploy them at the right time.

O. Students did byheart the main text, but applied it as well. Today, getting students to apply and crack a HOTS question is a herculean task for all teachers.

O. They studied more for learning than for writing the exam. Today, I cannot imagine a school in India not setting aside time for revision before an ordinary school test!

O. The wisdom of the main text sank in. They conducted themselves according to `Dharma’ ( A term that cannot be translated because it is not religion but a sense of right and wrong). Today wisdom must be treated to mean a complete understanding of concepts where students know not just the application but also its value. They must be in a position to know its impact and what the world would be without it.

O. The system also gave them a livelihood, which is probably the only thing we focus on today. Values have replaced `Dharma’ and have been reduced to a one period a week textbook style lesson.

O. The main texts related to mathematics and science also brought in spirituality or at least the idea of Dharma.

In their philosophy, good education should be `arthakari’, provide a livelihood, `muktahkari’, show a pathway to liberation, which can be interpreted today as the wisdom of understanding the value of their education, and `Yukthakari’, or teach them the strategies and skills to plan and execute tasks in personal as well as work life, which can be called life skills. We need to understand that value education was not a stand alone component, but it drove towards a spiritual trajectory in life which automatically gave values. Spiritual as against religious needs to be underlined, because all religions basically teach how salvation can be attained, through techniques, pathways, commandments or similar prescriptions.

How did the system lose out and how do we bring it back? With the intervention of British education, the ecosystem of Gurukuls were destroyed. The government used to fund panchayats and temples, a portion of which was provided for education. Over and above that society used to fund them. The funding was cut off and replaced by the current model. The main text was replaced by a textbook. So instead of learning the Vedas or the treatises by heart, students learned the textbook back to back. This perhaps is the origin of `rote memorisation’ that we are often accused of and have still not grown out of. All this is retained in India, while the western system has grown by leaps and bounds with fresh research.

We cannot bring the system back in its pristine form, what with the current demands and the population explosion. What we can do is introduce elements which we feel are suitable. Instead of teaching these elements as additional content, we can adapt them as pedagogical tools, which is what Contemplative Learning Prakriya is attempting to do, so that they can be used in any language or any system. CLP, for short, is in the process of converting some of the main texts such as Arthashastra, or a Kathopanishad as learning cards that teachers can give students to use as guide, a function the main text used to do. Sanskrit and Tamil have treatises and books that deal with every single discipline in such a way that they combine spirituality with the concepts of the discipline, be it Shilpa Shastra or material science, Governance or Geography, Mathematics or Chemistry, Agriculture of Ayurveda.

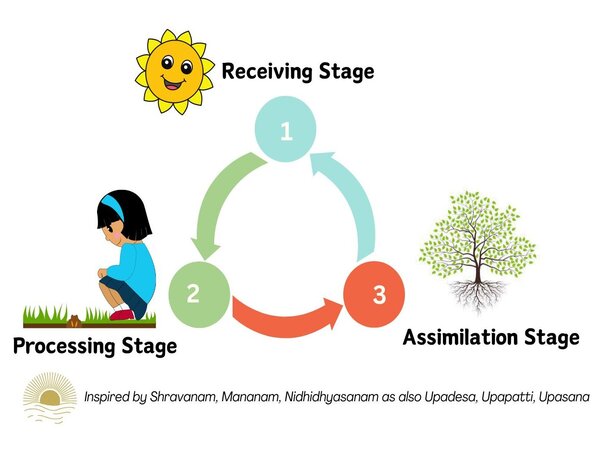

CLP has developed surveys to detect the nature of a student based on the Gunas, like Tamas, Rajas, Sattva, which is a great indicator for career guidance as well as a great way to provide study guidance and differentiate in the classroom. Learning is divided into three part cycles where they can gather information, employ all the methods mentioned above , applying, debating, discussing etc. It will overlap here with modern education. But when they assimilate and contemplate it will go beyond what the current system envisages. This is where they will grow in wisdom and depth of understanding.

The introduction of a universal statement that will peg the contemplation of children is its speciality, for instance a statement like the Kural no 423. `எப்பொருள் யார்யார்வாய்க் கேட்பினும் அப்பொருள் மெய்ப்பொருள் காண்பதறிவு’. ( Knowledge is seeing the real meaning of anything no matter what anyone says about it.) While reflecting through their experience they use this and prove it with reason. Thus the growth of wisdom as well as values. There are several statements like this in many Indian languages and that wealth can be used to teach children to imbibe values. For instance, the derivation of universal statements from the Sanskrit Mahavakya `Aham Brahmasmi’ to say that ` All things in the universe are interconnected’.

Assessment can happen the way it is now but it will go beyond by marking imprints which are basically indicators of the student’s attitude and inclinations which will help predict their learning behaviour in future. All this however, is possible only when they do and learn, not when they read textbooks and learn. In the chalk and talk method students are reduced to a non entity. But in the project method, students are alive exercising all their freewill and it becomes evident to the teacher what they can do instead of what they cannot do.

CLP is a work in progress and I have a team working on it. Thanks to their passion and dedication, it is taking shape. I have developed a diploma programme for teachers and am waiting for formal affiliation and am authoring a book on it. I was called in to make a presentation on this recently in a conference called `Dharma in the Digital Age’. The irony is, it happened in America, in the city of Atlanta hosted by a foundation called Dharma Civilization Foundation. It took place at Georgia Tech University. The layers of interpretation that the word Dharma has, was presented to the audience by an American and the correct way to represent Indian Gods and Goddesses was also presented by an American artist.

Bibliography

Books

Adi Shankara – Vivekachoodamani, Apaokshanubhuti

Bhagavad Gita

Bourai H H A – Indian Theory of Education

Johari, Harish – Dhanwantari

B Mahadevan, Vinayak Rajat Bhat, Nagendra Pavana R N – Introduction to Indian Knowledge Systems

Mukherjee, Radha Kumud – Ancient Indian Education

Pattanaik, Devadutt – Dharma Artha Kama Moksha

Swami Satchidananda – Commentary of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

Swami Sarvapriyananda – YouTube channel, Vedanta Society, New York

Singh, Sahana – The Educational Heritage of Ancient India, Revisiting the Educational Heritage of India

Thiruvalluvar – Thirukkural

Web Based References

Anubandha Chatushtaya – https://www.sivanandaonline.org/?cmd=displaysection§ion_id=801

Mahadevan B – Taittiriya Upanishad

Upanishad Ganga TV Series

Traditional Yoga – https://www.swamij.com/

Several papers published in journals such as those from Benaras Hindu University, Vinoba Bhave University and blogs by practitioners

Mrs. Nithya Sundaram – Academic Director, CS Academy Schools